There is now a museum attached to the castle, as you can see in the photo above. It has several exhibits, including one on the natural wildlife of Norwich (much the same as you see in the Pacific Northwest--same climate), 18th-century clothing, modern watercolor paintings, Anglo-Saxon artifacts, an Egyptian mummy, the Margaret Fountaine butterfly collection, and Boudica, a Celtic queen of the East Anglian Iceni tribe who led a brutal revolt against the occupying Romans in A.D. 60 or 61, among other exhibits.

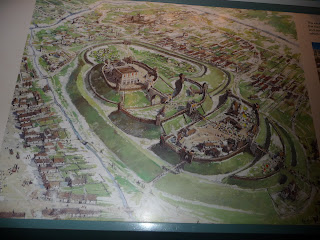

There is now a museum attached to the castle, as you can see in the photo above. It has several exhibits, including one on the natural wildlife of Norwich (much the same as you see in the Pacific Northwest--same climate), 18th-century clothing, modern watercolor paintings, Anglo-Saxon artifacts, an Egyptian mummy, the Margaret Fountaine butterfly collection, and Boudica, a Celtic queen of the East Anglian Iceni tribe who led a brutal revolt against the occupying Romans in A.D. 60 or 61, among other exhibits. Here, we have a drawing of what the castle looked like in the 12th century. The first outer bailey is now the location of Castle Mall shopping center, and the other baileys are still hills, but have business buildings all over them.

Here, we have a drawing of what the castle looked like in the 12th century. The first outer bailey is now the location of Castle Mall shopping center, and the other baileys are still hills, but have business buildings all over them. From the 1220s to 1887, the castle was used as a prison. There's a lot of scratched graffiti on the stone walls from the prisoners. The oldest one dates back to the 13th or 14th century! This is a model of what the prison looked like in 1887. In 1895 it opened up as a museum, and all of the little gray buildings were demolished.

From the 1220s to 1887, the castle was used as a prison. There's a lot of scratched graffiti on the stone walls from the prisoners. The oldest one dates back to the 13th or 14th century! This is a model of what the prison looked like in 1887. In 1895 it opened up as a museum, and all of the little gray buildings were demolished.

Here are two views from inside the keep. The bottom floor is divided in half, with one half being a museum for the 1067-1220 "castle" era, and the other half being devoted to the 1220-1887 "prison" era. During the "castle" time, the top floor was completely solid--you couldn't look down and see the bottom floor. There were also wooden walls dividing the space up into rooms, though, as you can see, those are all gone now. The far corner in the second picture is the area that used to be the castellan's chambers (or king's, when he chose to visit).

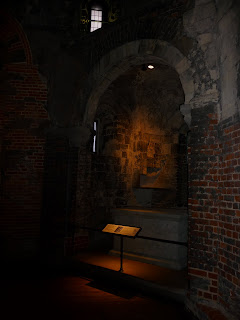

Here are two views from inside the keep. The bottom floor is divided in half, with one half being a museum for the 1067-1220 "castle" era, and the other half being devoted to the 1220-1887 "prison" era. During the "castle" time, the top floor was completely solid--you couldn't look down and see the bottom floor. There were also wooden walls dividing the space up into rooms, though, as you can see, those are all gone now. The far corner in the second picture is the area that used to be the castellan's chambers (or king's, when he chose to visit). Also on the second floor is an altar, built for the king's private use. It's called the Royal Peculiar, and iss unusual because it was consecrated and controlled by the king, not the Archbishop of Canterbury, which means that only the king has the power to unconsecrate it. It can still be used for weddings, baptisms, etc., because it's still holy ground. During the "prison" years, it was used to baptize children born in jail and give Last Communion to those about to be executed.

Also on the second floor is an altar, built for the king's private use. It's called the Royal Peculiar, and iss unusual because it was consecrated and controlled by the king, not the Archbishop of Canterbury, which means that only the king has the power to unconsecrate it. It can still be used for weddings, baptisms, etc., because it's still holy ground. During the "prison" years, it was used to baptize children born in jail and give Last Communion to those about to be executed. Opposite the alter are the latrines, shown here. Some poor peasant was hired to clean out the nasty business regularly so that it wouldn't stink up the whole castle. The perk was that, if anyone were to drop a ring or some such down the latrines by accident, the royal pooper scooper was allowed to keep it, no questions asked.

Opposite the alter are the latrines, shown here. Some poor peasant was hired to clean out the nasty business regularly so that it wouldn't stink up the whole castle. The perk was that, if anyone were to drop a ring or some such down the latrines by accident, the royal pooper scooper was allowed to keep it, no questions asked.During the prison days, the latrine was used as an infirmary--a rather disturbing thought, in my opinion. Norwich Castle was one of the only prisons to have an infirmary for several centuries--usually they didn't really care if a prisoner got sick or died, since they weren't really adding to society anyway.

A grand and roomy doorway; one of several. The idea was that if you made the doorways really small, invaders could only attack one by one and would thus be much easier to kill.

A grand and roomy doorway; one of several. The idea was that if you made the doorways really small, invaders could only attack one by one and would thus be much easier to kill.

This well is in the near-center of the main floor. It's 124 feet deep and dates from the end of the 11th century.

A detail of the grand entrance. I took some photos of the whole entrance, but they weren't much to look at. The carvings make it one of the best secular carved medieval doorways in England. The petal-looking carvings on the outer strip are Norman-style stars, to symbolize the heavens. The seed pod/coffee bean looking things in the next strip are symbols of the Virgin Mary (apparently "secular" is a loose term), and the inner strip has carvings of hunting scenes--the kind done for sport, not meals.

A detail of the grand entrance. I took some photos of the whole entrance, but they weren't much to look at. The carvings make it one of the best secular carved medieval doorways in England. The petal-looking carvings on the outer strip are Norman-style stars, to symbolize the heavens. The seed pod/coffee bean looking things in the next strip are symbols of the Virgin Mary (apparently "secular" is a loose term), and the inner strip has carvings of hunting scenes--the kind done for sport, not meals.

At the other end of the attached section of the museum is a staircase that leads down to a tunnel. The tunnel is decked out like a WWI trench, complete with sound effects. At the other end lies the Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum, which was also fun to look through. It had a section for each war since at least the War of the Roses, if not the Battle of Hastings, all the way up to the Iraq War. It's interesting--the British accounts of wars are a lot less biased than the ones you get in American museums. It's still there, definitely, but not nearly as much. They're also a lot more willing to admit when they lost a war. They've got so many wars that they've won and/or done well in that admitting few losses here or there over the centuries doesn't really bother them. It was really interesting to see the section on the American Revolution and read about the heroes on the British side--they rarely if ever mention them in the American history textbooks. On a separate but somewhat related note, there is a building on campus named after Thomas Paine, which I find incredibly ironic.

No comments:

Post a Comment